An essay I wrote in 2010…

Abstract

The purpose of this report is to explore the key technological developments in the sound and motion picture industry from the early beginnings in the late 1800’s to todays’ complex digital technology. I propose to present my findings on the history of this subject including the devices used for recording, editing and projecting sound along with their forgotten pioneers.

Introduction

In this report I am going to discuss the evolution of technology of sound recording, production and projection in the motion picture industry.

Although we think of films as essentially a visual experience we cannot afford to underestimate the importance of sound in that experience. Thomas Edison’s research and inventions of the moving image were originally intended to serve as visual accompaniment to recorded sound.

When sound was finally synchronized to motion pictures successfully in the 1920’s, films received a new life; actors could talk, music could convey emotional impact and sound effects added realism. The popular belief is that Warner Brother’s The Jazz Singer is the first film with sound but it actually is the first film with sound that was commercially accepted.

There have been many innovations in the way sound has been recorded, edited and amplified for the film industry, my aim is to address the innovations of the gradual evolution of sound-synch technology.

Development History

In 1887 Edison invented the tin foil phonograph, the first device that played back recorded sound. This was in essence a diaphragm mounted with a steel needle which recorded sound vibrations in the grooves of a cylinder.

By the end of 1888 Edison had his improved cylinder phonograph on the market which didn’t deteriorate as much as the tin foil phonograph. Edison conceived of his Kinetoscope (1891) as an optical counterpart to the phonograph. To Edison, the motion picture was a visual addition to the phonograph. Edward Kellog explains that

Edison invented the motion pictures as a supplement to his phonograph, in the belief that sound plus a moving picture would provide better entertainment than sound alone. But in a short time the movies proved to be good enough entertainment without sound. It has been said that although the motion picture and the phonograph were intended to be partners, they grew up separately. And it might be added that the motion picture held the phonograph in such low esteem that for years it would not speak. Throughout the long history of efforts to add sound, the success of the silent movie was the great obstacle to commercialization of talking pictures. (Kellog, E. 1951, quoted Ulano, M. 01.11.10)

In 1886 a device called the Kinetophone was invented by Auguste Baron which combined sound and visual scenes. Microphones installed above a set were connected to a separate sound booth where the transmitted signals were engraved in copper. A single motor drove the camera and the phonograph simultaneously at the same speed. Baron with the help of Felix Mesguich set up a studio in which he shot four-minute-long films of people singing in 1898. Baron would soon abandon his work due to lack of financial support.

The French Lumiére Brothers had begun the first commercial projections in 1895. Apart from live musical accompaniment of dialogue and effects, the synchronization of the phonographic cylinder with film was not very successful for two main reasons, firstly phonographs were not sufficiently sensitive in recording- actors had to position themselves very close to the phonographic horns which were therefore visible in the shot- nor were they powerful enough for reconstituting the sound and secondly the synchronization of the phonograph and the projector during projection was still very rough. This led to further experiments in the early 1900’s such as producer Léon Gaumont who had his actors record their text on the cylinder and then act in front of the camera whilst moving their lips in time to the recording.

Henri Joly experimented with the recording of sound on the image track itself but it was electro- acoustical engineer Eugene Lauste who conceived a system for the optical recording of sound on a narrow band alongside the image on film instead of on a cylinder.

The first movies shown to large audiences were silent movies which actually were rarely silent. A piano accompanied the projection in order to cover the sounds of the projector and to emphasize the emotional effects of the film. Each cinema would have a lecturer who both animated the show and ensured that its content was understood as well as important dialogue or explanations of actions. Sounds were also imitated to enhance the effects of actions or moods.

By 1913 there were two big problems in the sound film industry- synchronization and amplification. Edison failed to find the solution to projecting synchronized sound and moving image which caused the giving up of the idea of talking pictures and the success of silent movies. Harry Geduld summarizes the attempts of the early 1900’s;

Carl Laemmle imported Jules Greenbaum’s Synchroscope from Germany in the summer of 1909 and British film pioneer, Cecil Hepworth brought out his Vivaphone in 1911. In fact, no fewer than a dozen other manufacturers tried to market competing systems during this period. Names like Cinematophone (1907), L.P. Valiquet’s Photophone (1908), Animatophone (1910) and Orlando Kellum’s Photokinema filled the trade journals with claims of perfection in the art of talking pictures. (Geduld, 1975)

In 1926 a major break-though occurred that revolutionized the entire industry. Warner-Brothers in conjunction with Western Electric introduced a new sound-on-disc system called Vitaphone. Sound effects and music were recorded onto a wax record that was later synchronized with the film projector. The first feature-length film that exhibited this technology released by Warner Brothers was Don Juan which had synchronized sound effects and a pre-recorded score. It did not have spoken dialogue.

Fox in conjunction with General Electric invented a system called Movietone. This was the first commercially successful sound-on-film system which added a ‘soundtrack’ directly onto a strip of film. This method is called the Tri-Ergon Process which converted sound into light beams which were recorded onto the film strip then reconverted to sound in the projection process. This system replaced the Vitaphone system soon after because it was easier to synchronize the sound.

The first feature-length talkie was The Jazz Singer released by Warner Brothers in 1927. Although it only had about 350 spoken words, it was a box office hit and revolutionized the industry by causing the beginning of real commercial acceptance of sound, music and dialogue to films.

Talkies had the effect of initially stiffening the mobility of the actors because they could only move from one microphone to another which would have been hidden for example in a flower arrangement. The camera movement skills developed in the silent era became for a short while compromised but within a few years techniques such as the booming of a microphone (a microphone on the end of a long stick held above the actors out of shot) and post production dubbing were developed.

Fantasound

In 1940 the first multichannel format film Walt Disney’s Fantasia was released. This film is a benchmark as important innovations in sound technology arose from this which include: the click track, pan-pot, overdubbing of orchestral parts, dispersion-aligned loudspeaker system with skewed-horn, control-track level-expansion, simultaneous multitrack recording and the development of a multichannel system.

Leopold Stokowski conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra which were recorded on eight optical recorders which allowed sections of the orchestra to be handled separately during mixdown, a new concept at the time. A special system was devised for playback of Fantasia called Fantasound. This used two projectors- one projected the picture and had a mono optical mix of the entire soundtrack. This mono mix was a backup for the main soundtrack. This technique is still used today in all successful digital sound systems. The second projector employed four mono optical sound tracks as follows: 1. control track; 2. screen left; 3. screen right and 4. screen center. Fantasound led to a variety of magnetic techniques and eventually to Dolby Stereo.

Disney’s chief engineer, William Garity had the challenge of trying to simulate sound moving back and fourth across the screen. He determined that fading between two speakers might create this illusion. He created a device called “The Panpot” which was a special 3-circuit differential junction network which enabled Disney to mix down to a three track master. Mixdown was performed much like a modern film scoring session as Stokowski conducted pans and level changes in real time. Many consider the panning to be “ping-pongy” but one may forgive this for bringing the Panpot into existence.

Fantasia was re-released several times until 1990. In 1956 (the third release) the four track magnetic format was mixed in stereo but had no surround information. The 1982 release had a brand new soundtrack recorded by Shawn Murphy on a Soundstream four track digital recorder using a sampling rate of 50kHz which had better fidelity than was possible in the Forties but had a inferior performance and much more radical panning than the original. For the 1990 re-release Disney’s Terry Porter cleaned up the magnetic master track (the optical master disappeared) eliminating 3000 pops, hum, noise and distortion. Porter then did a Dolby Stereo SR mix of the cleaned up tracks.

Progression of Monophonic Sound to Quadraphonic Sound

It was in the 1950’s that stereophonic sound (the division of sound across two channels, left and right) became industry standard rising from monophonic sound (one channel) and Fantasound. Stereophonic sound enabled the listener to experience the correct sound staging of an orchestra recording where certain sounds emanated from different parts of the stage however, monophonic elements are also included for example when a vocalist is singing from the “phantom” center channel. Stereophonic sound does have limitations such as some recordings having a “ping-pong” effect (when too much mixing into the separate channels has occurred) and a lack of ambience.

The late 1960’s and early 1970’s brought Four Channel Discrete and Quadraphonic Sound. Four Channel Discrete was extremely expensive as it need four identical amplifiers to reproduce sound. Quadraphonic sound was a more successful approach to sound reproduction because it was a format that consisted of a matrix encoding four channels of information within a two channel recording. This was in essence the forerunner of today’s Dolby Surround.

Dolby Surround

In the mid-70’s Dolby Labs (founded by Ray Dolby), with breakthrough film soundtracks such as Tommy, Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, unveiled a new surround sound process called Dolby Surround Sound. The Dolby Surround process involves encoding four channels of information- Front Left, Center, Front Right and Rear Surround into a two channel signal. A decoding chip then decodes the four channels and sends them to the appropriate destination, the Left, Right, Rear, and Phantom Center. The result of Dolby Surround mixing is a more balanced and realistic listening environment in which the main sounds derive from the left and right channels, the dialogue emanates from the center channel and the ambience comes in from behind the listener. Unlike quadraphonic sound, Dolby Surround quickly gained marketplace acceptance.

Dolby have gone from strength to strength through the years with innovative technology including Dolby Pro Logic (which adds more accuracy to explosions, planes flying overhead etc), Dolby Digital (known as a 5.1 channel system where the .1 designation refers to the subwoofer channel) and Dolby Digital EX (where sound directionality are more precise).

Today Dolby have moved to the next generation of surround sound- Dolby Digital Plus. The benefits include superior audio quality, up to 7.1 channels of theatre-quality sound which unlocks the full audio potential from Blu-ray Discs, HD broadcasts to ensure the listener hears audio precisely as it was intended.

On-Location Recording and Production

Film soundtrack begins with location recording. Great sound supports and enhances the story the film maker is trying to tell and subconsciously draws the audience into what they are viewing. The better the soundtrack, the less it is consciously noticed.

Preproduction planning is essential so that excessive ambient noises are dealt with appropriately, checking the boom operator and production crew have enough space to move without compromising the picture. Plan which microphones are suitable for the subject to be recorded. The positioning of the microphone(s) is also important. Every operational and technical need must be anticipated, important equipment and materials include; tape, back-up microphones, cables, connectors, mic accessories, clip leads, AC power checker, glues, flash light, pen and paper, recording tape, pocket knife, stopwatch, tape measure, tool kit, headphones, log sheets, scripts and rundown sheets.

Recording and Synchronization of Sound

The quality of location tape recorders have improved dramatically through the years. The leading professional field recorder is manufactured by NAGRA Audio- Kudelski Group who have developed and marketed a complete range of analogue and digital tape recorders. Nagras are appreciated for their sound quality, reliability and ruggedness. Their physical appearance with the single transport selector and reel-to-reel tape deck are still the stereotypical image most people have of the professional tape recorder.

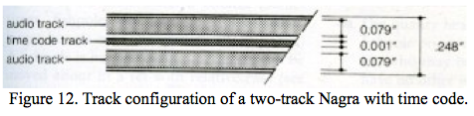

In 1951 Stefan Kudelski invented the Nagra (meaning “will record” in Polish) which was revolutionary- a portable audio tape recorder that was light, small, portable and high quality. In 1962 the Nagra III was equipped with Stefan Kudelski’s “Neopilot” system which replaced the “Pilloton” system, this resulted in better synchronization of audio recordings with moving pictures and became the industry standard until the 1980’s. The 1970’s a miniature version (the Nagra SNN) was designed to be a pocket recorder for cinema actors to carry and used cassette width 1/8th inch tape. The Nagra IV-S allowed musical performances to be captured in stereo in a portable format using a revolutionary frequency modulated central track for commentary or pilot information. This device had dual level pots, limiters and equalizer pre-sets. The Nagra IV-S Time Code is seen as benchmark in terms of sound recording for cinema productions and has been used on film sets all over the world.

Timecode provides a time reference for editing, synchronization and identification. SMPTE time code is an industry standard frame numbering system that labels a specific number to each frame of video in the format of hours, minutes, seconds and frames as defined by the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers in the SMPTE 12M specification. SMPTE time code is important for accuracy and repeatability, every frame of video is given its own unique identifying number. Once recorded, that time code/video frame relationship will be the same every time the tape is played. In 2008 SMPTE revised the standard set in the 1960’s and now have a two part document: SMPTE 12M-1 and SMPTE 12-M2 which includes important new explanations and clarifications.

Due to the flexibility of production and postproduction equipment and time code, it is possible to record on location using the multi-camera or single-camera production style regardless of the medium for which the production is being made. The invention of time code made video editing possible and led to the invention of non-linear editing systems.

Postproduction

Postproduction is the final stage in the production process when all previously recorded material is edited and mixed. Editing is an art which demands the ability to see a complete work and build towards it while it is still in small parts. Editing is a tedious job whether it is done in an manual or computer environment yet seldom gets recognition except professionally because a good edit is never heard therefore it is known as an “invisible art”.

In linear editing recorded material is edited successively on a film positive (not the original negative): one section at a time is physically cut from one part of a tape or magnetic film and pasted to another part using a splicer and threading the film on a machine with a viewer such as a Moviola or flat-bed machine such as a Steenbeck. The work is very physical and done by ear.

The Steenbeck (patented in 1934) is an analogue film editing machine which works with continuously variable elements (light and sound waves), inscribed in a durable object (film). It holds picture and sound film reels and has a two-picture screen which allows the editor to preview and edit before cutting the film. It is available in 16mm and 35mm or a combination of the two formats.

Nonlinear editing (also known as random access editing) is a digital process that allows one to assemble a sound file in or out of sequence and take it from any part of a recording and place it at any point of the recording at the touch of a button. Today this is done digitally using specialized software such as Avid or Lightworks on IBM, Macintosh or Atari computers.

Analog Versus Digital

Both methods of editing are reliable yet very different to each other causing a split in film makers who each stand by their preferred process. Editor Tom Rolf misses “having the film in [his] hands, around [his] neck, in [his] mouth” (Weiner 26). An interesting argument is “Human beings are incapable of observing digital information in the same way that they observe continuous analog information” (Goodell 183). Therefore, “an image or sound that has been translated into digital information must be translated back into analog for us to hear or see it” (Goodell 183).

Pro-digital editors claim the Steenbeck machine is obsolete and editing on a computer is safer and quicker. No longer do editors have to wait days for the edit to come back from the laboratory plus no edit decision can ruin or distort the original information.

Amplification Developments

Reproducing recorded sound to a large audience was a major issue in early cinema. In the early 1920’s Dr. Lee Forest invented Audion vacuum tubes which amplified the sound coming out of a speaker without causing distortion. In 1925 a loudspeaker invented by Edward Kellog and Chester Rice surpassed its predecessors in sound quality. This was the first moving coil cone loudspeaker with an electrically energized magnet system. In 1927 Bell Telephone Laboratories produced a horn loudspeaker as John Aldred describes with

a moving coil mechanism driving a diaphragm and a powerful magnet system with a battery energized field coil. This gave a power efficiency as high as 25% which enabled sound to be reproduced at much higher levels and with improved quality. This was important since the amplifiers at that time only had an output of 2 watts. The driver unit was attached to an exponential horn, curved so as to conserve space behind the screen, and multiple throats which allowed 2 or more units to be attached for increased output. (Aldred, J. 27.11.2010)

Equalization (the balancing of frequencies) was introduced in 1931 into theatre amplifiers and new power tubes became available that were cable of giving 8 watts.

Edward Sponable became aware of the high background noise of photographic sound tracks and together with Western Electric he invented noise reduction systems. In 1938 the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences set up a committee to study the standardization of theatre sound equipment and the acoustics of theatre spaces.

The 1950’s saw the introduction to multi-tack magnetic sound from Cineamascope, Cinerama and 70mm release prints which led to the standardization of loudspeakers being changed in the 1960’s as John Aldred explains to:

two 15in diameter bass units in a reflex cabinet (available in several sizes), and high frequency horns (also available in several sizes) with multi-cellular flared openings. Large auditoria would have two bass cabinets bolted together for each channel, with side wings to increase the baffle area,and two or more high frequency horns. (Aldred, J. 27.11.2010)

Today 6 out of 10 Dolby equipped movie theatres worldwide are fitted with JBL loudspeakers making JBL the industry standard. JBL are unparalleled in experience with nearly eighty years in the industry and are famous for their high quality components. JBL loudspeakers also grace the stages of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Samuel Goldwyn Theatre, The Directors Guild of America and The Academy of Television Arts and Sciences.

Conclusion

This report has described the various innovations in multichannel cinema from the early beginnings of Edison’s phonograph to today’s modern digital technology. The industry is however currently going through the transition from analogue to digital. There is great choice for budding film editors today as both methods are being taught to students around the world.

I am personally excited to see what the digital age will bring next as I prefer working with virtual information because I always have the option of hitting “undo” if I make a mistake and the entire process (in my view) is more specific than analogue. Nonetheless I understand and respect if it wasn’t for the old methods none of todays effects we take for granted would have been invented.

With exciting digital technology available today we can expect multichannel cinema to become richer and ever more varied with time.

References

ALDRED, J. (n.d.) 100 Years of Cinema Loudspeakers [WWW] About. Available from: <http://inventors.about.com/gi/dynamic/offsite.htm? site=http://www.amps.net/newsletters/issue21/21_cine.htm> [Accessed 27.11.10]

GEDULD, H.M. (1975) The Birth of the Talkies. University of Indiana GOODELL, G.(1998) Independent Feature Film Production: A Complete Guide From Concept

Through Distribution. 182-183. St. Martin’s Press, 1998. KELLOG, E. (1951) The Journal of the SMPTE. Society of Motion Picture and Television

Engineers.

ULANO, M. (n.d.) Moving Pictures That Talk [WWW] Film Sound. Available from: <http://www.filmsound.org/ulano/talkies2.htm> [Accessed 01.11.10]

WEINER, R. (1994) “The Cutting Edge Finds Converts.” Variety. 26. June 27, 1994 – July 3, 1994. Reed Elsevier Inc., 1994.

Bibliography

ALTEN S. (1994) Audio in Media, 4th ed. California: Wadsworth Publishing Company AMYES, T. (1990) The Technique of Audio Post-Production in Video and Film. London: Focal

Press BLAKE, L. (1984) Film Sound Today. Hollywood: Reveille

BROCKETT, D. (2002) Location Sound: The Basics And Beyond. [WWW] Kenstone. Available from: <http://www.kenstone.net/fcp_homepage/location_sound.html> [Accessed 28.11.10]

CHARACTERCONTROL (1943) Sound Recording and Reproduction (Sound on Film). [online video] Available from: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CRzjcb22yZA> [Accessed 15.11.10]

DANKER, N. (2008) A History of Sound Design in Film. [online video] Available from: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JgkAXcromkc&feature=related> [Accessed 15.11.10]

Dead Media Archive. (2007) Steenbeck. [online] Available from: <http://cultureandcommunication.org/deadmedia/index.php/Steenbeck> [Accessed 27.11.10]

FEASTER, P. (2009) Optical Sound Track Method. [WWW] Phonozoic. Available from: <http://www.phonozoic.net/ostm1.html> [Accessed 15.11.10]

KERNER, M. (1989) The Art of the Sound Effects Editor. Boston: Focal Press

MOVIE SNOBS (n.d.) Ten Reasons You Should Buy Blu Ray. [WWW] Movie Snobs. Available from: <http://www.moviesnobs.net/ten-reasons-you-should-buy-blu-ray/> [Accessed 28.11.10]

NAGRA (n.d) Professional Audio Products. [WWW] Nagra. Available from: <http://www.nagraaudio.com/pro/index.php> [Accessed 28.11.10]

RECORDING HISTORY (n.d.) The History of Recording Technology. [WWW] Recording History. Available from: <http://www.recording-history.org/> [Accessed 01.11.10]

SOUND TECHNOLOGY (2010) News. [WWW] Sound Technology Ltd. Available from: <http://www.soundtech.co.uk/jbl/news/> [Accessed 15.11.10]

THE AMERICAN WIDESCREEN MUSEUM SOUND STAGE (2000) Telling the Story of Sound Motion Pictures Through Contemporary Writings. [WWW] The American Widescreen Museum. Available from: <http://www.widescreenmuseum.com/sound/sound04.htm> [Accessed 01.11.10]

TOULET E. (1988) Cinema is 100 Years Old. Trieste: New Horizons